A distant quasar’s black hole is oddly huge for its galaxy

The dim gap powering the quasar has a file mass relative to the stars of the host galaxy

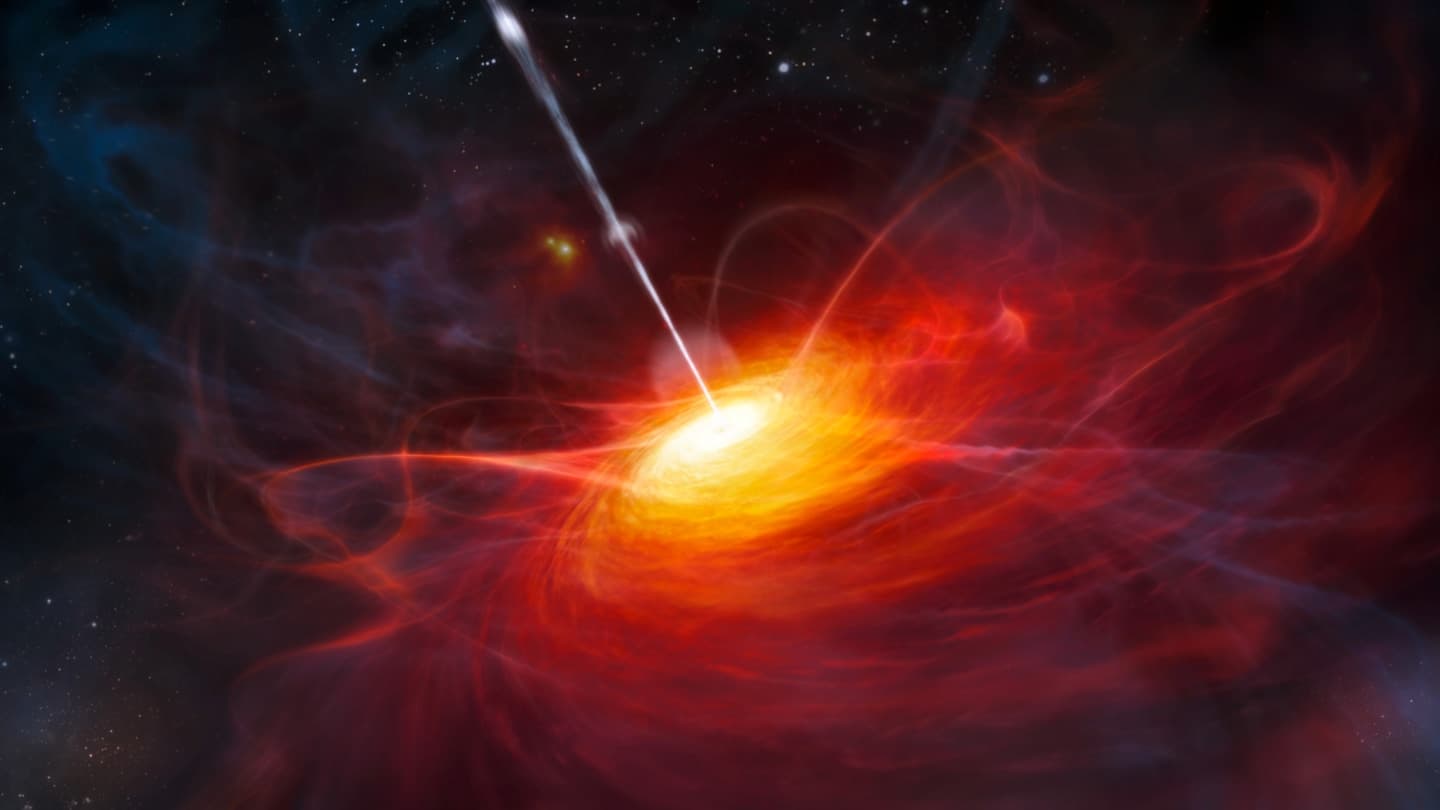

The 1.4-billion-photo voltaic-mass dim gap powering a remote quasar named ULAS J1120+0641 (illustrated) within the constellation Leo is half as big as the stars within the surrounding galaxy, a ratio bigger than that viewed in any diversified quasar host galaxy.

M. Kornmesser/ESO

The first-ever sighting of starlight from a galaxy net net hosting one in all primarily the most distant quasars diagnosed has published a gigantic oddity.

Quasars — blazingly colorful galactic cores — owe their brilliance to the intense warmth that results as gasoline whirls around a gigantic dim gap. The dim gap powering a quasar 13 billion gentle-years from Earth is half as big as all of the stars around it — a file excessive ratio for a quasar host galaxy, astronomers narrative in a paper submitted October 14 to arXiv.org.

All old attempts to gaze the host galaxy with the Hubble Dwelling Telescope failed. So astronomers took draw with the James Webb Dwelling Telescope, or JWST, as an different (SN: 6/20/23).

The quasar, named ULAS J1120+0641 and the fourth farthest diagnosed, outshines its galaxy bigger than 100 cases over (SN: 6/29/11). “This makes it very laborious to measure the [light] from the host galaxy,” says group member Minghao Yue, an astronomer at MIT. Nonetheless for the length of the 13 billion years that the quasar’s gentle has sped toward us, the universe’s expansion has stretched the gentle waves by bigger than 700 percent. Thus, we peek the quasar’s visible gentle at infrared wavelengths, where JWST conducts most of its observations.

The dim gap powering the quasar, the astronomers derive, is 1.4 billion cases as big as the solar, in accordance with old estimates. What’s contemporary is the detection of the host galaxy, whose stars add up to 2.6 billion photo voltaic plenty. That’s minute when put next with the Milky Manner, whose stellar mass is some 60 billion photo voltaic plenty. Nonetheless on the time we peek the quasar, about 750 million years after the Tall Bang, all galaxies had been younger, and even a variety of the supreme galaxies had fewer stars than common giants love our have.

What truly jumps out is the relative heft of the dim gap: It weighs in at 54 percent of its galaxy’s stellar mass, versus handiest about 0.1 percent for central dim holes in common wide galaxies. “Meaning the coevolution between dim holes and their hosts within the early universe needs to be very diversified” from common galaxies, Yue says.

Harvard University astronomer Avi Loeb is of the same opinion. He thinks the quasar’s radiation has suppressed star formation within the host galaxy by heating its gasoline (SN: 8/16/24). To give design and win stars, interstellar gasoline needs to be frigid; in every other case, the outward push of thermal stress prevents the gasoline from collapsing into contemporary stars. “If I needed to bet,” he says, “the gasoline is now not frigid enough to scheme lots of stars.”

The quasar will shut off in its future, Loeb says. Then the gasoline within the surrounding galaxy can cool and scheme stars, increasing the galaxy’s stellar mass. If we might maybe maybe peek the galaxy as it is some distance this day, its dim gap mass relative to its stellar mass might maybe maybe totally match that of big galaxies near us.

Unfortunately, Yue says, the contemporary work doesn’t address the thriller of how these enormous dim holes grew so big so rapidly after the Tall Bang (SN: 1/18/21). Nonetheless the observations attain heed every other galaxy colliding with the one net net hosting the quasar. The collision presumably spills gasoline into the dim gap, boosting its already truly huge mass and in addition lighting up the quasar so as that astronomers can peek it across the kind of big distance.

More Tales from Science Recordsdata on Dwelling